Why the first 100 days can make or break your startup

The first 100 days of a startup are not just another chapter in a company’s journey; they are the opening act that sets the tone for everything that follows. While it is tempting for founders to think of the first months as a trial period with plenty of time to course-correct later, history suggests otherwise. Decisions made, priorities set, and habits formed in those early days have a lasting impact. They shape culture, define credibility, and often determine whether the venture builds momentum or stalls before it truly begins.

Why should founders care so much about this early period? Because the beginning of a startup is the most malleable stage in its life. Once scale sets in — whether in team size, product complexity, or customer base — course corrections are exponentially harder and more expensive. According to Investopedia, the majority of startups that fail do so because of preventable mistakes: poor market research, insufficient capital planning, or weak operations. Most of these weaknesses can be traced back to what was (or was not) addressed in the very first months.

What Happens in the First 100 Days

In the first month, founders are expected to lay down the foundations. This means handling legal and financial structures, clarifying the problem they aim to solve, and identifying the customers they intend to serve. It is also the moment to define culture and values within the founding team, because the way a startup communicates and collaborates in its early days often endures for years.

The second phase, from days 31 to 60, is where the focus shifts toward building a minimum viable product. The “lean startup” method, widely popularized by Eric Ries and explained on Wikipedia, suggests that startups must get a working version of their product into the hands of users as quickly as possible. It doesn’t need to be polished, but it must be testable, usable, and capable of generating real feedback. Startups that spend these weeks locked in a room perfecting a product without customer input often find they have built something people don’t actually want.

By the final stretch, days 61 through 100, the expectation is to demonstrate momentum. That may mean onboarding the first paying customers, securing initial contracts, refining product features based on user feedback, or showing retention among early adopters. For many founders, this is also when they begin to approach investors, and evidence of traction in the first 100 days becomes a powerful signal of execution ability.

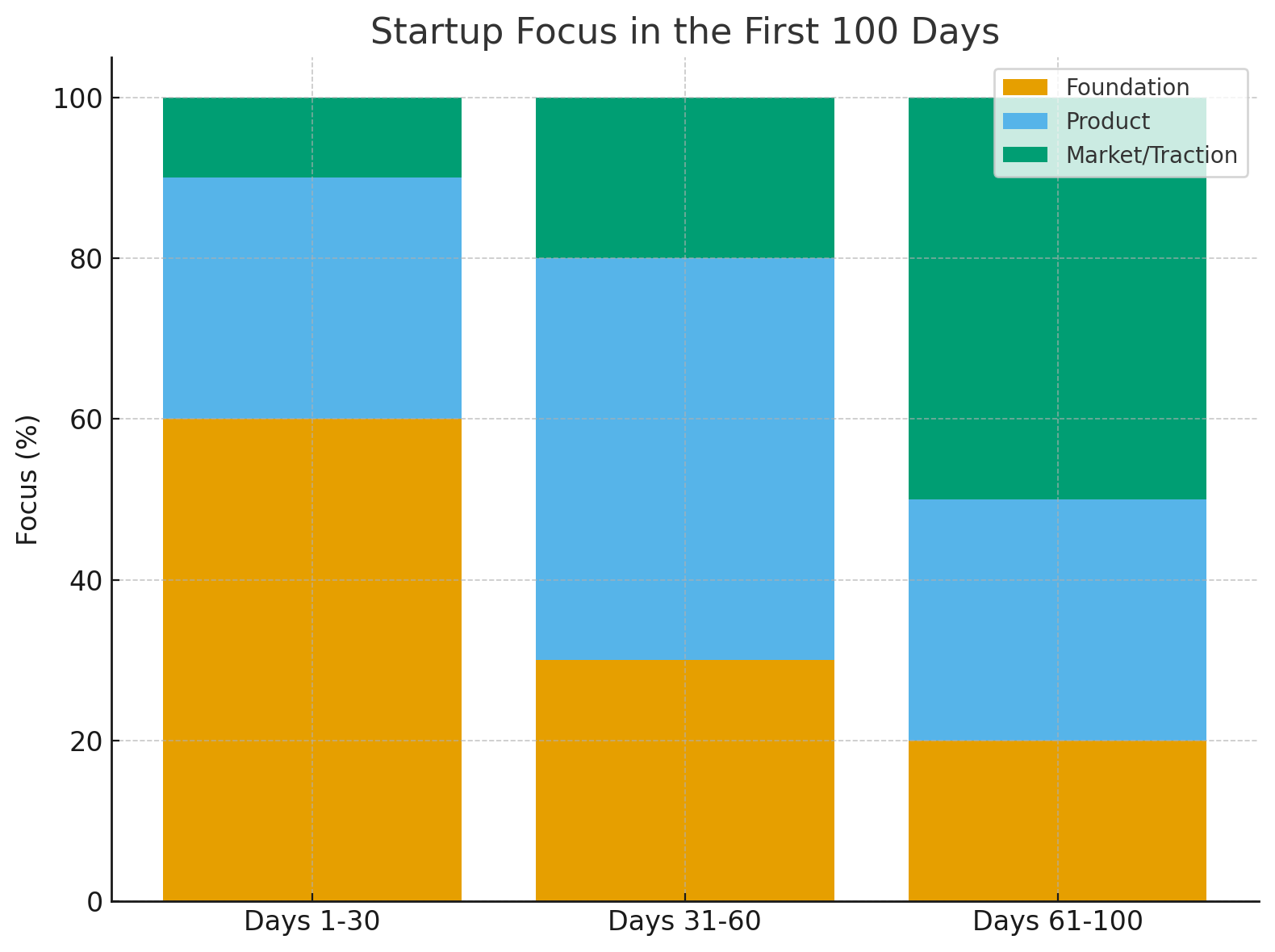

The following chart illustrates how a startup’s focus typically evolves across these three phases, moving from foundation to product to market traction:

In the earliest weeks, foundation work dominates. As the startup progresses, attention tilts toward building and refining the product. By the end of the first 100 days, market traction takes precedence. This shift underscores a key principle: while legal, financial, and cultural structures are necessary, they are only valuable if they support a product that real people want to use and are willing to pay for.

Stories of Startups That Navigated the First 100 Days

The experience of early-stage companies provides both cautionary tales and inspiration. Consider Leyr, a digital health startup whose founders openly documented their first 100 days on Medium. They spent the period conducting market research, building and testing an MVP focused on patient scheduling, and aligning the team on vision and culture. By deliberately prioritizing learning and feedback over scaling, they positioned themselves for longer-term traction and fundraising. Their progress may not have been headline-grabbing, but the discipline in those early days helped prevent wasted time and resources.

Contrast that with Homejoy, once a promising home-cleaning marketplace that attracted major funding. As Wired reported, Homejoy rushed into expansion before establishing reliable quality control or sustainable unit economics. Although its early days saw rapid growth in new cities, the startup never fixed its core customer retention problem. Lawsuits and high churn eventually drove it to shut down. The lesson: early traction can be deceptive if the fundamentals are not addressed within the first 100 days

Some startups manage to capture remarkable momentum in those first weeks. Drop (formerly Massdrop) is a classic example. As First Round Review recounted, the company generated $12,000 in its first week of operations, $25,000 in the second, and $50,000 in the third. The product itself was imperfect, but early revenues proved that customers valued it enough to pay. This early validation was crucial in securing investor confidence and laying the groundwork for rapid scaling.

Another perspective comes from Entrepreneur, which collected stories from founders across industries. One described how securing initial customer orders within the first 100 days not only generated early revenue but also gave the company negotiating leverage with suppliers. These stories highlight that the first months are not only about testing ideas but also about creating credibility with both customers and partners.

Why the First 100 Days Can Make or Break a Startup

The importance of the first 100 days extends beyond immediate traction. Early users often become the foundation of word-of-mouth marketing. Positive first impressions turn into testimonials, referrals, and case studies that amplify credibility. At the same time, early missteps in customer experience can leave lasting reputational damage.

Cultural norms also crystallize in this period. How decisions are made, how conflicts are resolved, and how founders prioritize time are all patterns set early. Once ingrained, they are difficult to change. That is why founders are advised by experts like Daedalium to focus obsessively on customer retention and product-market fit before worrying about scale.

The first 100 days are also when operational risks are most manageable. Legal compliance, tax structures, data practices, and financial planning might seem like distractions compared to product development, but neglecting them early can lead to crippling problems later. Founders who delay setting up sound operations often face costly corrections when growth introduces complexity.

A Roadmap Without Checklists

While it is tempting to reduce the first 100 days to a neat checklist, the reality is messier. Each startup will experience these days differently depending on sector and product type. A biotech company, for instance, cannot deliver an MVP in 100 days the way a consumer app can. In deep tech or regulated industries, the first 100 days are more about prototyping, research, and regulatory preparation than user acquisition. What matters across all sectors, however, is that the period is used to establish discipline, learn quickly, and make visible progress.

Rather than a checklist, it is better to think of the first 100 days as three overlapping arcs. The first arc is about foundation — incorporating, structuring finances, and clarifying the problem. The second is about product — designing, building, and iterating on something usable. The third is about the market — finding early adopters, demonstrating retention, and showing momentum.

Conclusion

The startup journey is unpredictable, but the first 100 days are uniquely consequential. They are the periods when the cost of mistakes is lowest and the return on good decisions is highest.

Founders who treat these early months as a chance to build discipline, validate assumptions, and earn credibility often find themselves better equipped for the long road ahead. Those who waste them chasing vanity metrics, skipping foundational work, or ignoring customer feedback risk setting their companies on a path to failure.

The lesson is simple but vital: the first 100 days are not about perfection, but about momentum. Ship something, learn something, build trust, and prove — if only in small ways — that the idea has a reason to exist. Everything else flows from there.

Read - Why the Next Big Startup Wave Must Go Beyond AI: The Case for Non-AI Innovation

square.jpg)